Break the Cycle - Stick it to Putin by Decreasing Demand for Oil, Part 2 of 3

Break up with your toxic boo and move on for good.

If you haven’t read Part 1 yet, please start there!

First Things First

But, Honestly…Change is Hard…and Humans Are Genetically Resistant to It

According to Emerson Human Capital Consulting:

We are hardwired to resist change. Part of the brain—the amygdala—interprets change as a threat and releases the hormones for fear, fight, or flight. Your body is actually protecting you from change.

Boldface mine. Seems important. Emerson goes on to talk about Gleicher’s Formula, which states that three factors determine if you can overcome the psychological costs of change that keep you chained to existing habits:

Dissatisfaction with the way things are now

A positive vision of the future

Concrete steps to make the vision a reality

Gleicher’s Formula is:

D x V x F > R … or

Dissatisfaction x Vision x First Concrete Steps > Resistance

In other words, we have to:

Be really not-OK with life as-is

Be able to see a plausible future, and

Know how to get there

When taken together, those have to overcome the status quo (the resistance), and I think this is the problem for us. There’s been no big push politically because…gas isn’t the drain on the pocketbook as many say or think it is:

“Dissatisfaction with the way things are now” just hasn’t been that high because, well, it didn’t hurt that badly. Don’t tell me what you value. Show me your budget and I’ll tell you what you value. You know gas prices aren’t killing you, so you’re not making or demanding changes to bring them down (for the country or your pocketbook).

Had Enough?

But think about this near future:

There could be a multi-year war in eastern Europe

One of the combatants is one of the top-5 oil-producing states in the world

You’ll have no direct, immediate control over oil prices

The USA’s involvement in the war likely makes it a lot worse

Your angry protest votes in 2022 and 2024 won’t help anyway

I ask because, if you’re not OK with that, I’m here to help you:

Be able to see a plausible future and

Get from here to there

And even if you don’t see the forest here…who wouldn’t pick up $3,000 in crisp Benjamins if it was sitting on the sidewalk in front of them???

So, if we can cut back on oil usage by identifying suitable alternatives that don’t really inconvenience us much (or at all), why the heck would we not do it?

Other than stubbornness, why not? We’re in a toxic relationship. We need to get out. Seriously.

Why Do I Bother Taking Some of My Weekend to Write About This?

My family has two cars - a Toyota Prius v (hybrid) and a Prius Prime (plug-in hybrid). We all have Hop Card transit passes through TriMet (the Portland metro’s transit agency), and all of us have bikes (though, truly, only my son and I use them, and he mostly uses mine…). We live in a dense-ish suburb west of Portland, OR. We’ve made the transition, mostly because the oil-price swings give me hives. Our last step is to replace our Prius hybrid with an EV when it dies.

Many of my hives came from when we lived in Palm Coast, FL, which is a very car-centric, very pedestrian- and bike-unfriendly, transit-free city between Daytona Beach and St. Augustine. We made very middle-class incomes while there, and we worked, for the most part, in Daytona Beach, which was 33 miles south. I talk about our experience in FL here:

For most of our time in FL, we owned a 2003 Ford Focus SE sedan and a 2006 Ford Freestyle. Both were standard internal-combustion vehicles. We drove, together, about 22,000 miles per year.

I also happened to grow up in Burnsville, MN, in the 1990s.

Burnsville is also very car-centric, though more pedestrian- and bike-friendly than Palm Coast, and it does have some transit (downtown-express buses to/from Minneapolis, then some slow buses to various other places from park ‘n’ rides), though I’m not sure I’ve ridden a MSP-area bus since I was about 8 (I’m 44).

Oh, and #skol.

So, I’m not some latte-sipping lib that “wouldn’t know a real American” or whatever stupid trope someone is going to throw at me on Twitter (though I like lattes and am a lib). I just wasn’t always this guy. I grew up in a conservative family 🤷♂️ I have, in fact, had to work for a living for at least some of my life 😜 I remember gas prices being a serious annoyance in 2008 (our gas budget was as high as $450/month) and thinking “there’s gotta be a better way”.

Stating It for the Record: No One is Asking You to Live on a Farm and Ride Horses Until You Die

Well, maybe not no one, but no one of significance.

“Use less oil, y’all” isn’t the same as “we can’t have nice things”. Let’s not be dramatic. With technologies and infrastructure available today, you can make significant changes to your consumption habits but still live in your city or suburb - heck, some of the options I’ll discuss apply even if you do live on a farm - and shuttle your kids to school, go grocery shopping, or go out to dinner, all while still having nice things. We don’t need “degrowth” to use less oil.

We have options to get around that don’t involve one person driving in a gas-powered vehicle literally everywhere…or everyone growing their own food and riding horses. You can cut usage at the margins or go all in. It all depends on your budget, how busy you are, and your appetite for change. Some of these options have wider uses than others but all are sound to reduce your use of oil at least a little. Remember:

So, I’m here to show you a possible future and how to get there, and break up with your toxic ex.

When You Need a New Car, Decrease Demand By Getting a More-Efficient One

Getting rid of a perfectly good car just to save on gas will almost never be worth it unless gas is $10-12/gallon. The payoff period is too long, especially if you take on a car payment. So, don’t junk your working 2011 Subaru Outback just to save a few grand a year on gas. However, if it dies, your life circumstances change, or if you’re just bored with it and can sell it for a decent price, replace it with a more-efficient option using some newer technology. Replacing Car A with more-efficient Car B is the easiest way to do this because it requires very little change to your habits other than just learning how to drive the new car properly, which is pretty easy (the dealership will usually help you).

Below are the most-plentiful options, all of which are, in fact, nice things.

Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs)

These have been around over 20 years now and should be familiar to just about anyone. Here’s how a Toyota hybrid engine works, though most others will work similarly:

The most famous of the hybrids is the Toyota Prius…

As you can see, they’re priced at…about the same as a similar gas-powered car now, yet their mileage is about 2x. There are tons of hybrids out there now - sedans, coupes, SUVs, even a couple of pickups. Even the 2022 Ford Maverick Lariat pickup gets about 40 mpg and will cost you in the $25-35K range.

Just about every manufacturer has one or more hybrids for sale (though not all). Just go to your favorite search engine, then type in your favorite car manufacturer plus “hybrid” and see what comes up (here’s Ford). You’ll probably find something you like.

The downside of some hybrids is that they can be a little underpowered, from what I can tell. This is true of our 2014 Prius v. We got used to it quickly, though. Most of the time this doesn’t matter but if POWER! is your thing, research and do a little test driving to find a good fit for you.

Also, keep reading for better options.

Most PHEVs and EVs Qualify for Federal Tax Credits and/or State Rebates

Here’s a link to all EV and PHEV federal tax credits in 2022. Read on for more.

Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs)

A PHEV is - depending on the make & model - either:

A combination of an electric vehicle and a standard internal-combustion engine (ICE)

A combination of an electric vehicle and a hybrid engine

The battery on these usually lasts for 20-40 miles, after which the gas-powered or hybrid engine kicks in. We have a Prius Prime, and it’s the kind in the second bullet above (EV + HEV). Here’s how the Toyota PHEV engines work:

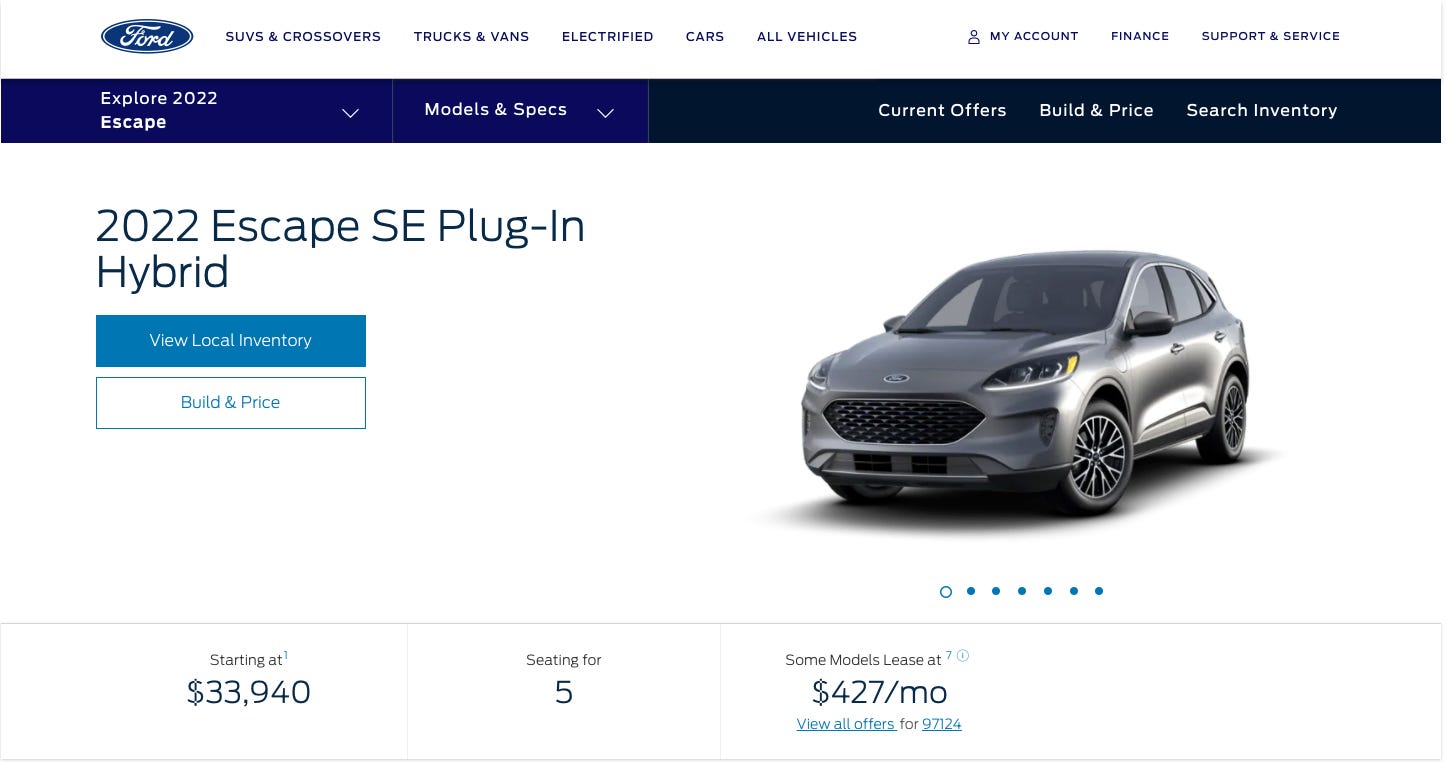

Here’s one such example:

These fancy guys are only a little pricier than their pure-hybrid brethren but…

For most city driving, you’re not using gas much at all, meaning you rarely leave EV mode (i.e.: You’re driving a de facto EV in town)

In EV mode, these suckers accelerate, and they’re really quiet

They burn about 1/3 to 1/4 of the gas of a standard ICE (we’re getting about 175 mpg on ours over 15 months of ownership - we spend about $10/month to gas it up and $15/month to charge it)

Maintenance is pretty low

They still qualify for federal and state high-efficiency-vehicle incentives, whereas most conventional hybrids no longer do (they phase out after some number are sold in the USA). The incentives for the vehicle above are sizable, which actually makes it cheaper than the standard hybrid on the same chassis.

We own an older version of the Prius Prime and these were our incentives.

Ford’s 2022 Escape is also available as a PHEV (est. 40 mpg):

Here is Car & Driver’s list of every PHEV on sale as of last month’s issue.

You do have to plug them in routinely to charge the battery but it’s not as urgent as a pure EV because you have a gas backup. It’s just better on your pocketbook (and harder on ol’ Vlad!).

So, if you’re like my wife, you like the idea of an EV but would find yourself chewing off your fingernails every time your EV battery got below 50 miles remaining. In this case, maybe consider a PHEV instead so you have that backup gas. We fill our tank up about 4x/year.

Electric Vehicles (EVs)

Alright, these are all the rage right now and, if you ask me, it’s probably warranted. EVs have come a long way in just a few short years, and new manufacturers and models are coming online every day (not all will survive, of course), offering ranges as high as 500 miles on a charge (though most are 200-350 miles).

Here’s essentially how they work:

Here is Motortrend’s list of every EV on sale as of January. Here are some Car & Driver expects to see on the market soon. One of the more-affordable EVs is the Nissan Leaf:

A fancier, longer-range one is the Tesla Model 3:

Tesla and other manufacturers offer many others and some fall into the “luxury” category. Most don’t.

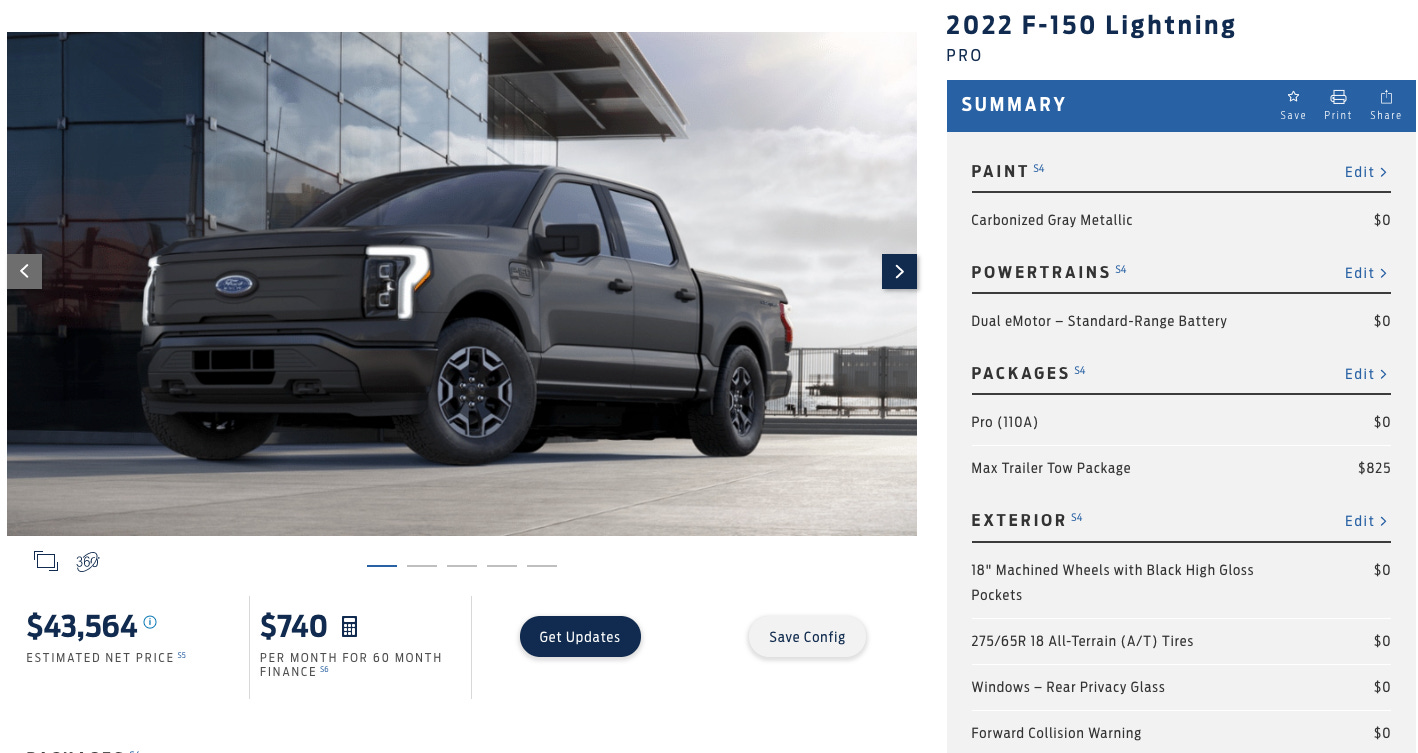

And, of course, Ford just came out with the 2022 F-150 Lightning pickup EV, which has a 230-mile range and 426 horsepower. I priced out a “Pro” model with a trailer-towing package ($825). Here’s the cost before a $10,000 rebate package ($7,500 federal tax credit + $2,500 Oregon rebate) but including destination charge (1,700). No factory incentives.

I’ve ridden in a Tesla, have co-workers that own Leafs, and have driven a Polestar. All EVs have some serious get-up-and-go behind them (think really big golf carts), so you won’t be disappointed. Plus, now that there are pickups in the game, I doubt many have an excuse not to make the switch.

Oh, and most get those big EV credits & rebates, too. Google “[your state] rebate EV 2022” to find out your state incentives. NOTE: Federal tax credits apply to each model of EV, so many Tesla models no longer qualify due to sales volume to date. Talk to a salesperson for details.

Charging an EV

The part of owning an EV that scares some people off is the need to charge it. Well, yeah, you have to do that. It’s part of owning an EV, and this is no different than asking “how often will I need to get gas?” or “will I make it to the next gas station before running out?” The difference, obviously, is that you don’t really “go to the gas station” as much as “plug it in for the night/afternoon/trip to the mall”. You don’t go to the gas station every day, but you likely will plug in your EV at least a couple of times per week. At home. Probably overnight. In short, it’s not that big of a deal unless you’re driving long distances. Honestly.

Remember: Change is hard. Your brain is telling you to be scared. It’s a shift in your driving paradigm. You aren’t learning to fly. It’s still a car/truck.

Either way, the speed of charge depends on:

The capacity of the car’s driving battery - the longer the range, the longer the charge time

The charging station’s amperage & voltage

If you have a short range, a good charger isn’t all that necessary. But if you have a long-range EV - or you’re impatient, regardless of your vehicle - you’ll want a better charger.

There are public-use EV-charging stations popping up at shopping areas, public buildings, and even some healthcare facilities, and these offer a charge for a pretty low fee. You’ve probably seen stations from Tesla, Blink, Volta, ChargePoint, SemaConnect, etc. You’ll also likely want to install one at home, as your current 110V electrical setup probably isn’t optimized for it. Just consider this part of the cost of doing business. It’ll run you, unit + installation, somewhere in the $1,000-2,000 range, depending on the bells & whistles and/or how powerful you want to get. I just got an estimate to purchase and install two EV chargers, as well as the 220V line, in my garage (anticipating the EV coming in a few years) and the total was…$1,300. I can even get a rebate from our power company to offset some of that cost.

One really nice part of EVs, though? You rarely need to maintain them. Electric motors are simple. No cylinders, coolant, gas tank, exhaust, etc. Just big RC car motors.

If you’re interested, go to a local car dealer and test-drive one if you have a few hours. Ask your questions about charging, etc. They’re much less nerve-wracking - and much more fun - than you’d think.

Second, Decrease Demand By Just…Driving Less, When Able

This is the cheapest way to reduce demand…but it takes a little thought and maybe some adventurousness, depending on the situation. I’m going to skip obvious options such as carpooling or combining trips and focus on individual-trip replacement.

The goal: Drive maybe 90% as much as you did before. This saves some gas and sticks it to Vlad. You may even get some exercise out of the deal!

When you feel yourself thinking…

The parking lot at my destination is crazy

The traffic on the route is terrible

Buses and trains are regularly passing me while I sit in traffic

The drive is risky/dangerous/boring/long

I could literally walk/bike and not lose much time

I don’t need to fill up a trunk or carry anything really heavy

It’s a beautiful day and I’d enjoy the trip / I have time to spare

Look at your options below and think, “could I use one of those options instead of driving?”

Human-Powered Options

Walking is the most-obvious and natural way to get from A to B. You also don’t need equipment other than good shoes and socks. Consider a walk if time isn’t critical and the distance is under a mile. If you can get yourself one of these bad boys ($90), you can even go shopping (we used to get a trip to the farmers’ market and grocery store with one):

If you need to go 5 miles of your less for work or light-duty errands, buy a bike of your choosing and then get a rear rack…

…hang a pair of cargo panniers on that rack (there are other options) so you can do some quick grocery shopping, hit the liquor store, stop at Walgreens, etc:

Panniers actually hold more than you think. I think I’ve made an $80 grocery run in the past that included a gallon of milk and a half-gallon of half-and-half. Anyway, bike + rack + panniers are you’ve got yourself yourself a little cargo bike. If you want to get a little more power from your pedal strokes, install some pedal toe clips for cheap:

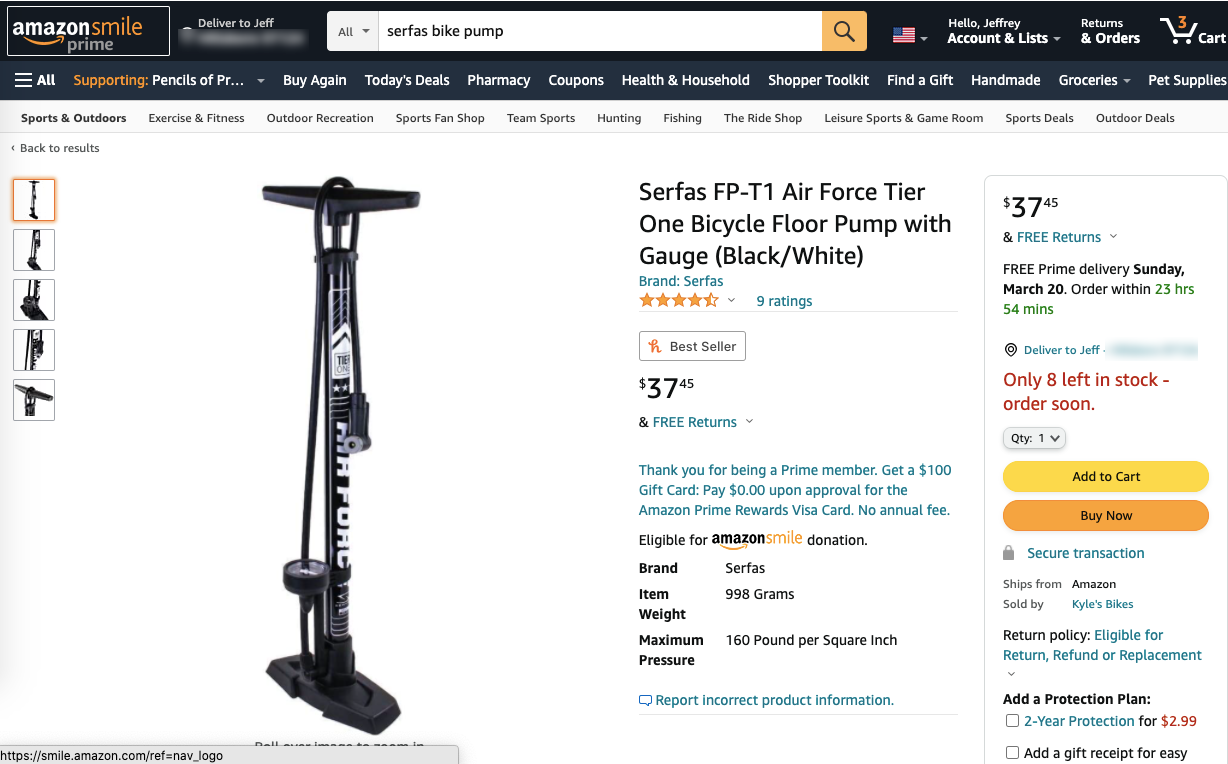

If you don’t have an air compressor with a gauge already, get a hand-powered bike pump so you can quickly keep your tires inflated:

Everything I listed above comes to $200-250.

Now…beyond bikes, I’ve seen others use skateboards or - my personal favorite - rollerblades (inline skates for you non-hockey-playing heathens), but those are just for true believers. Stick to walking and biking :)

Options That Use Electrons

E-Bikes

If you’re more of the “hey, I like electricity!” type and want your bike to have a little boost to it, you could do almost everything in the bike section above but use an e-assist bike instead of a human-powered one. This article was published on 3/11/2022 (in light of high gas prices) and gives you plenty of cheap options available now. Here’s a commuter/in-town bike whose battery hides in the frame and gives you e-assist for 20-30 miles:

This allows you to bike but do so using less personal energy, and you might even be able to go a little faster while you’re at it. Of course, you’ll pay for this convenience and extra performance - a similar non-electric bike would run you $450-700 - but it beats the hell out of paying $5/gallon for gas!

Electric Scooters

While they don’t have the utility of a bike, they’re a lot faster than walking and easier than biking, and you can even use them in a bike lane. You may have seen some bopping around a number of areas lately, and some cities even have them for rent. However, if you have a backpack, you could easily make quick runs or commutes using one, which would greatly speed up a walk. They’re not pricey, either. For example, this one is a mere $390 on Amazon right now:

That sucker weighs 25 pounds, is street legal (lights on either end), has never-flat tires, folds up for carrying, charges in 3.5 hrs, and goes 11 miles on said charge at up to 18 mph. You could easily take these on transit or put them in a car/van, making them great “last mile” commute options.

Here’s a list of good electric scooters for sale in 2022. I kinda want one of these…

Party Like it’s 1899

Alright, this is the way for you to cut out the most demand: mass transit and intercity transportation. It also takes the most planning and, honestly, a bit of a lifestyle change, but for some of you, it probably makes a lot of sense, and reduces stress while you’re at it.

Intracity mass transit

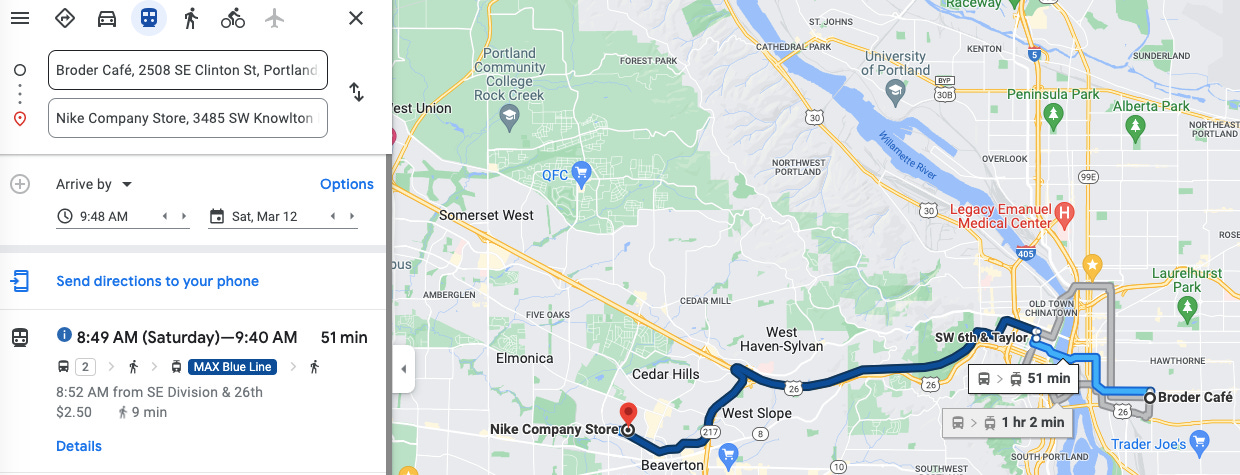

As with aircraft or intercity trains, mass transit usually serves larger, denser destinations and the points in between. A good network will get you access to a large area with one connection…or none. However, mass transit won’t work great for you if you’re trying to get from A to B but neither of those points is a populated area. But, if you have a good transit network in your area, Google Maps very likely includes directions from A to B. Just click the little train when you enter your directions to get your transit directions, which usually include some walking to and from stations or stops.

For example, if I want to go from to the Nike Company Store in Beaverton, OR, and live in Portland’s Inner Eastside, that traffic can kind of suck due to Portland’s geography. However, there’s a train line in the vicinity of the Nike store and buses in Portland. So, instead of trekking through town and burning dead dinosaurs, give TriMet a try. It’s a one-transfer trip (bus to train).

The time difference for a Friday morning going west isn’t huge.

In larger cities with worse traffic (and often in Portland during rush hour), the time alone can be similar (used to be a 5-minute difference for my morning commute). But from a financial perspective, if you remove the cost of gas, wear and tear on your car, and the risks you take by driving, the costs are probably similar. Oh, and you can read this article while you ride :)

Intercity Transit

If you need to go less than 500 miles between larger cities, consider using a long-haul service such as Amtrak or FlixBus, especially if your destination has good city transit. Maybe you’ve never used them, but these aren’t pricey options. Yes, the USA doesn’t have great options in some parts…but this is a big country. Some of the routes available are a bit much in terms of transit time for me, but some are downright reasonable and comfortable. They’re at least worth a look.

First, Amtrak. Outside of the Northeast, we don’t really have what I’d call “high-speed rail” in the USA. This isn’t Amtrak’s fault and more just its original founding sin, but there are good routes and you should become familiar. Amtrak itself has a route map that shows its key route structures in four regions.

I’ve used them quite a bit to travel among Portland, Eugene, and Seattle. It’s downright reasonable and pretty comfortable, too, and the prices are good, too. Here’s a Friday-to-Monday (late March) roundtrip itinerary (and I didn’t choose the cheapest):

Would I use Amtrak to travel 1,500 miles one way? No. But Portland-Seattle, Minneapolis-Chicago, LA-SF, or just about anywhere from DC to Boston? Yes.

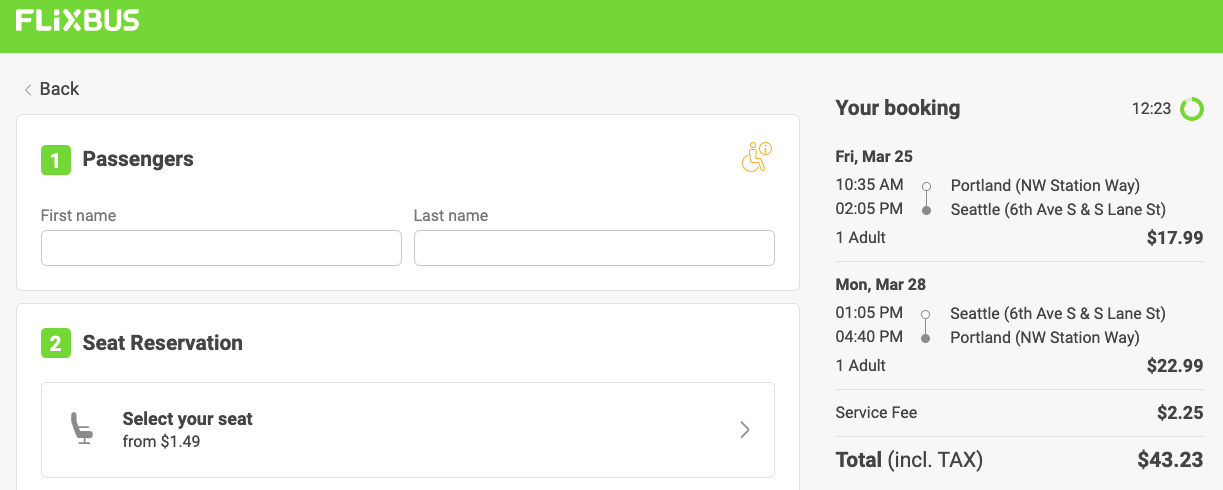

If your preference is roads instead of rails, give FlixBus (parent organization of Greyhound) a try. It’s more no-frills than Amtrak but, if you’re just in need of a ride from A to B, it works…and it’s pretty cheap.

I can get the same Portland-Seattle roundtrip (downtown to downtown), 3 hours in either direction, for about $43.

This is a 173-mile drive one way (346 miles roundtrip) and takes 2:41 if I left now. If I were to drive a 2018 Ford Edge (29 mpg highway) on this, I’d use 11.9 gallons. At $4.50/gallon, that’s $53.69. So:

I don’t have to drive

It takes me an extra 20 minutes

I save $10

I mean, I’ll call that a win.

You Have Options

At the end of the day, cutting back on oil usage is possible, and in many cases even practical. You can make your regular trips use less of it or you can replace some of your short or long trips, or you can do both. You just need to decide that you’re done with the toxic relationship and cut it off for good.

Trust me, you’ll be happy you did.

This is great detail Jeff, thank you for your work on this.